what advances were made in the field of medicinal chemistry during the period from 1700 to 1900?

This timeline of chemistry lists important works, discoveries, ideas, inventions, and experiments that significantly changed humanity's understanding of the modern science known as chemistry, defined every bit the scientific report of the limerick of affair and of its interactions.

Known every bit "the key scientific discipline", the study of chemistry is strongly influenced by, and exerts a strong influence on, many other scientific and technological fields. Many historical developments that are considered to have had a significant impact upon our modernistic agreement of chemical science are also considered to have been cardinal discoveries in such fields as physics, biological science, astronomy, geology, and materials scientific discipline.[1]

Pre-17th century [edit]

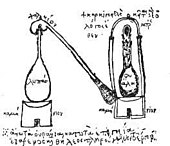

Ambix, cucurbit and retort, the alchemical implements of Zosimus c. 300, from Marcelin Berthelot, Drove des anciens alchimistes grecs (three vol., Paris, 1887–88)

Prior to the acceptance of the scientific method and its application to the field of chemical science, it is somewhat controversial to consider many of the people listed below as "chemists" in the modernistic sense of the word. However, the ideas of sure nifty thinkers, either for their prescience, or for their broad and long-term acceptance, bear listing hither.

- c. 450 BC

- Empedocles asserts that all things are equanimous of iv primal roots (later to be renamed stoicheia or elements): globe, air, fire, and water, whereby 2 active and opposing cosmic forces, dear and strife, act upon these elements, combining and separating them into infinitely varied forms.[ii]

- c. 440 BC

- Leucippus and Democritus propose the idea of the atom, an indivisible particle that all thing is fabricated of. This idea is largely rejected by natural philosophers in favor of the Aristotlean view (run across below).[three] [4]

- c. 360 BC

- Plato coins term 'elements' (stoicheia) and in his dialogue Timaeus, which includes a discussion of the composition of inorganic and organic bodies and is a rudimentary treatise on chemistry, assumes that the minute particle of each chemical element had a special geometric shape: tetrahedron (fire), octahedron (air), icosahedron (h2o), and cube (earth).[v]

- c. 350 BC

- Aristotle, expanding on Empedocles, proposes thought of a substance as a combination of matter and class. Describes theory of the Five Elements, fire, water, world, air, and aether. This theory is largely accepted throughout the western world for over g years.[6]

- c. 50 BC

- Lucretius publishes De Rerum Natura, a poetic description of the ideas of atomism.[vii]

- c. 300

- Zosimos of Panopolis writes some of the oldest known books on alchemy, which he defines as the study of the composition of waters, movement, growth, embodying and disembodying, drawing the spirits from bodies and bonding the spirits within bodies.[eight]

- c. 800

- The Clandestine of Creation (Arabic: Sirr al-khalīqa), an anonymous encyclopedic work on natural philosophy falsely attributed to Apollonius of Tyana, records the earliest known version of the long-held theory that all metals are equanimous of various proportions of sulfur and mercury.[9] This same work besides contains the earliest known version of the Emerald Tablet,[10] a meaty and cryptic Hermetic text which was still commented upon past Isaac Newton.[11]

- c. 850–900

- Standard arabic works attributed to Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Latin: Geber) introduce a systematic nomenclature of chemical substances, and provide instructions for deriving an inorganic compound (sal ammoniac or ammonium chloride) from organic substances (such as plants, blood, and hair) by chemical means.[12]

- c. 900

- Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi (Latin: Rhazes), a Farsi alchemist, conducts experiments with the distillation of sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride), vitriols (hydrated sulfates of various metals), and other salts,[thirteen] representing the offset step in a long process that would eventually atomic number 82 to the thirteenth-century discovery of the mineral acids.[14]

- c. g

- Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī[15] and Avicenna,[xvi] both Persian philosophers, deny the possibility of the transmutation of metals.

- c. 1100–1200

- Recipes for the production of aqua ardens ("called-for water", i.e., ethanol) by distilling wine with common salt beginning to appear in a number of Latin alchemical works.[17]

- c. 1220

- Robert Grosseteste publishes several Aristotelian commentaries where he lays out an early on framework for the scientific method.[18]

- c 1250

- The works of Taddeo Alderotti (1223–1296) describe a method for concentrating ethanol involving repeated partial distillation through a water-cooled still, by which an ethanol purity of 90% could be obtained.[nineteen]

- c 1260

- St Albertus Magnus discovers arsenic[20] [ better source needed ] and silverish nitrate.[21] [ better source needed ] He also fabricated one of the starting time references to sulfuric acrid.[22]

- c. 1267

- Roger Bacon publishes Opus Maius, which among other things, proposes an early form of the scientific method, and contains results of his experiments with gunpowder.[23]

- c. 1310

- Pseudo-Geber, an anonymous alchemist who wrote under the name of Geber (i.e., Jābir ibn Hayyān, see higher up), publishes the Summa perfectionis magisterii, a book containing experimental demonstrations of the corpuscular nature of matter that was still being used by seventeenth-century chemists such as Daniel Sennert.[24] He is one of the first to describe nitric acid, aqua regia, and aqua fortis.[25]

- c. 1530

- Paracelsus develops the study of iatrochemistry, a subdiscipline of alchemy dedicated to extending life, thus beingness the roots of the modern pharmaceutical industry. It is besides claimed that he is the kickoff to use the word "chemistry".[eight]

- 1597

- Andreas Libavius publishes Alchemia, a prototype chemistry textbook.[26]

17th and 18th centuries [edit]

- 1605

- Sir Francis Bacon publishes The Proficience and Advancement of Learning, which contains a description of what would afterward be known as the scientific method.[27]

- 1605

- Michal Sedziwój publishes the alchemical treatise A New Calorie-free of Alchemy which proposed the existence of the "food of life" within air, much later recognized equally oxygen.[28]

- 1615

- Jean Beguin publishes the Tyrocinium Chymicum, an early chemistry textbook, and in it draws the kickoff-ever chemic equation.[29]

- 1637

- René Descartes publishes Discours de la méthode, which contains an outline of the scientific method.[30]

- 1648

- Posthumous publication of the book Ortus medicinae by Jan Baptist van Helmont, which is cited by some equally a major transitional work betwixt alchemy and chemistry, and as an important influence on Robert Boyle. The book contains the results of numerous experiments and establishes an early version of the law of conservation of mass.[31]

Championship folio of The Sceptical Chymist by Robert Boyle (1627–91)

- 1661

- Robert Boyle publishes The Sceptical Chymist, a treatise on the distinction between chemistry and alchemy. Information technology contains some of the earliest modern ideas of atoms, molecules, and chemical reaction, and marks the first of the history of modern chemistry.[32]

- 1662

- Robert Boyle proposes Boyle's law, an experimentally based description of the behavior of gases, specifically the relationship between pressure level and volume.[32]

- 1735

- Swedish pharmacist Georg Brandt analyzes a nighttime blue pigment found in copper ore. Brandt demonstrated that the pigment contained a new element, later named cobalt.[33] [34]

- 1754

- Joseph Blackness isolates carbon dioxide, which he called "fixed air".[35]

A typical chemical laboratory of the 18th century

- 1757

- Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt, while investigating arsenic compounds, creates Cadet's fuming liquid, later discovered to be cacodyl oxide, considered to exist the first synthetic organometallic compound.[36]

- 1758

- Joseph Blackness formulates the concept of latent heat to explain the thermochemistry of phase changes.[37]

- 1766

- Henry Cavendish discovers hydrogen as a colorless, odourless gas that burns and tin form an explosive mixture with air.[38]

- 1773–1774

- Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Joseph Priestley independently isolate oxygen, called by Priestley "dephlogisticated air" and Scheele "burn air".[39] [forty]

- 1778

- Antoine Lavoisier, considered "The father of mod chemical science",[41] recognizes and names oxygen, and recognizes its importance and role in combustion.[42]

- 1787

- Antoine Lavoisier publishes Méthode de nomenclature chimique, the get-go mod system of chemical classification.[42]

- 1787

- Jacques Charles proposes Charles'south police force, a corollary of Boyle'southward constabulary, describes relationship between temperature and volume of a gas.[43]

- 1789

- Antoine Lavoisier publishes Traité Élémentaire de Chimie, the showtime modern chemistry textbook. Information technology is a complete survey of (at that time) modern chemistry, including the first concise definition of the law of conservation of mass, and thus likewise represents the founding of the bailiwick of stoichiometry or quantitative chemical analysis.[42] [44]

- 1797

- Joseph Proust proposes the law of definite proportions, which states that elements always combine in pocket-size, whole number ratios to form compounds.[45]

- 1800

- Alessandro Volta devises the commencement chemical battery, thereby founding the discipline of electrochemistry.[46]

19th century [edit]

- 1803

- John Dalton proposes Dalton's constabulary, which describes human relationship between the components in a mixture of gases and the relative pressure each contributes to that of the overall mixture.[47]

- 1805

- Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac discovers that water is composed of two parts hydrogen and one office oxygen past book.[48]

- 1808

- Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac collects and discovers several chemical and physical backdrop of air and of other gases, including experimental proofs of Boyle'southward and Charles's laws, and of relationships between density and composition of gases.[49]

- 1808

- John Dalton publishes New System of Chemical Philosophy, which contains first modern scientific description of the atomic theory, and articulate description of the police of multiple proportions.[47]

- 1808

- Jöns Jakob Berzelius publishes Lärbok i Kemien in which he proposes modern chemic symbols and note, and of the concept of relative atomic weight.[50]

- 1811

- Amedeo Avogadro proposes Avogadro's police, that equal volumes of gases under abiding temperature and pressure contain equal number of molecules.[51]

Structural formula of urea

- 1825

- Friedrich Wöhler and Justus von Liebig perform the first confirmed discovery and caption of isomers, earlier named by Berzelius. Working with cyanic acid and fulminic acid, they correctly deduce that isomerism was caused by differing arrangements of atoms within a molecular structure.[52]

- 1827

- William Prout classifies biomolecules into their modern groupings: carbohydrates, proteins and lipids.[53]

- 1828

- Friedrich Wöhler synthesizes urea, thereby establishing that organic compounds could be produced from inorganic starting materials, disproving the theory of vitalism.[52]

- 1832

- Friedrich Wöhler and Justus von Liebig discover and explain functional groups and radicals in relation to organic chemistry.[52]

- 1840

- Germain Hess proposes Hess's law, an early on statement of the constabulary of conservation of energy, which establishes that free energy changes in a chemic procedure depend only on the states of the starting and production materials and not on the specific pathway taken betwixt the two states.[54]

- 1847

- Hermann Kolbe obtains acerb acid from completely inorganic sources, further disproving vitalism.[55]

- 1848

- Lord Kelvin establishes concept of absolute zero, the temperature at which all molecular motility ceases.[56]

- 1849

- Louis Pasteur discovers that the racemic course of tartaric acid is a mixture of the levorotatory and dextrotatory forms, thus clarifying the nature of optical rotation and advancing the field of stereochemistry.[57]

- 1852

- August Beer proposes Beer's law, which explains the relationship betwixt the composition of a mixture and the amount of light it will blot. Based partly on before work past Pierre Bouguer and Johann Heinrich Lambert, it establishes the analytical technique known as spectrophotometry.[58]

- 1855

- Benjamin Silliman, Jr. pioneers methods of petroleum cracking, which makes the unabridged modern petrochemical industry possible.[59]

- 1856

- William Henry Perkin synthesizes Perkin's mauve, the first constructed dye. Created as an accidental byproduct of an attempt to create quinine from coal tar. This discovery is the foundation of the dye synthesis industry, one of the primeval successful chemical industries.[60]

- 1857

- Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz proposes that carbon is tetravalent, or forms exactly 4 chemical bonds.[61]

- 1859–1860

- Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen lay the foundations of spectroscopy as a means of chemical analysis, which atomic number 82 them to the discovery of caesium and rubidium. Other workers shortly used the same technique to discover indium, thallium, and helium.[62]

- 1860

- Stanislao Cannizzaro, resurrecting Avogadro's ideas regarding diatomic molecules, compiles a tabular array of atomic weights and presents information technology at the 1860 Karlsruhe Congress, ending decades of alien atomic weights and molecular formulas, and leading to Mendeleev's discovery of the periodic police force.[63]

- 1862

- Alexander Parkes exhibits Parkesine, one of the earliest synthetic polymers, at the International Exhibition in London. This discovery formed the foundation of the modern plastics manufacture.[64]

- 1862

- Alexandre-Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois publishes the telluric helix, an early, 3-dimensional version of the periodic tabular array of the elements.[65]

- 1864

- John Newlands proposes the law of octaves, a precursor to the periodic law.[65]

- 1864

- Lothar Meyer develops an early version of the periodic table, with 28 elements organized by valence.[66]

- 1864

- Cato Maximilian Guldberg and Peter Waage, building on Claude Louis Berthollet's ideas, proposed the police force of mass action.[67] [68] [69]

- 1865

- Johann Josef Loschmidt determines exact number of molecules in a mole, later named Avogadro'south number.[seventy]

- 1865

- Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz, based partially on the work of Loschmidt and others, establishes construction of benzene as a six carbon band with alternating single and double bonds.[61]

- 1865

- Adolf von Baeyer begins work on indigo dye, a milestone in modern industrial organic chemical science which revolutionizes the dye industry.[71]

- 1869

- Dmitri Mendeleev publishes the first modern periodic table, with the 66 known elements organized past diminutive weights. The strength of his table was its ability to accurately predict the properties of as-however unknown elements.[65] [66]

- 1873

- Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Achille Le Bel, working independently, develop a model of chemical bonding that explains the chirality experiments of Pasteur and provides a concrete crusade for optical activity in chiral compounds.[72]

- 1876

- Josiah Willard Gibbs publishes On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, a compilation of his work on thermodynamics and physical chemical science which lays out the concept of free free energy to explain the physical basis of chemical equilibria.[73]

- 1877

- Ludwig Boltzmann establishes statistical derivations of many important concrete and chemical concepts, including entropy, and distributions of molecular velocities in the gas phase.[74]

- 1883

- Svante Arrhenius develops ion theory to explain conductivity in electrolytes.[75]

- 1884

- Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff publishes Études de Dynamique chimique, a seminal study on chemical kinetics.[76]

- 1884

- Hermann Emil Fischer proposes structure of purine, a primal construction in many biomolecules, which he afterward synthesized in 1898. Also begins work on the chemistry of glucose and related sugars.[77]

- 1884

- Henry Louis Le Chatelier develops Le Chatelier'south principle, which explains the response of dynamic chemical equilibria to external stresses.[78]

- 1885

- Eugen Goldstein names the cathode ray, afterward discovered to be composed of electrons, and the canal ray, later discovered to exist positive hydrogen ions that had been stripped of their electrons in a cathode ray tube. These would subsequently be named protons.[79]

- 1893

- Alfred Werner discovers the octahedral construction of cobalt complexes, thus establishing the field of coordination chemical science.[80]

- 1894–1898

- William Ramsay discovers the noble gases, which fill a big and unexpected gap in the periodic tabular array and led to models of chemic bonding.[81]

- 1897

- J. J. Thomson discovers the electron using the cathode ray tube.[82]

- 1898

- Wilhelm Wien demonstrates that canal rays (streams of positive ions) can exist deflected by magnetic fields, and that the amount of deflection is proportional to the mass-to-charge ratio. This discovery would lead to the analytical technique known as mass spectrometry.[83]

- 1898

- Maria Sklodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie isolate radium and polonium from pitchblende.[84]

- c. 1900

- Ernest Rutherford discovers the source of radioactive decay as decaying atoms; coins terms for various types of radiation.[85]

20th century [edit]

- 1903

- Mikhail Semyonovich Tsvet invents chromatography, an important analytic technique.[86]

- 1904

- Hantaro Nagaoka proposes an early nuclear model of the atom, where electrons orbit a dense massive nucleus.[87]

- 1905

- Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch develop the Haber process for making ammonia from its elements, a milestone in industrial chemistry with deep consequences in agriculture.[88]

- 1905

- Albert Einstein explains Brownian motion in a mode that definitively proves atomic theory.[89]

- 1907

- Leo Hendrik Baekeland invents bakelite, one of the first commercially successful plastics.[xc]

- 1909

- Robert Millikan measures the charge of individual electrons with unprecedented accuracy through the oil drib experiment, confirming that all electrons accept the same accuse and mass.[91]

- 1909

- S. P. L. Sørensen invents the pH concept and develops methods for measuring acerbity.[92]

- 1911

- Antonius van den Broek proposes the idea that the elements on the periodic table are more properly organized past positive nuclear accuse rather than diminutive weight.[93]

- 1911

- The outset Solvay Briefing is held in Brussels, bringing together nearly of the most prominent scientists of the solar day. Conferences in physics and chemical science continue to be held periodically to this day.[94]

- 1911

- Ernest Rutherford, Hans Geiger, and Ernest Marsden perform the gilded foil experiment, which proves the nuclear model of the atom, with a small, dense, positive nucleus surrounded past a diffuse electron cloud.[85]

- 1912

- William Henry Bragg and William Lawrence Bragg advise Bragg'south law and establish the field of 10-ray crystallography, an important tool for elucidating the crystal structure of substances.[95]

- 1912

- Peter Debye develops the concept of molecular dipole to describe disproportionate charge distribution in some molecules.[96]

The Bohr model of the cantlet

- 1913

- Niels Bohr introduces concepts of quantum mechanics to atomic structure by proposing what is now known as the Bohr model of the atom, where electrons be but in strictly defined orbitals.[97]

- 1913

- Henry Moseley, working from Van den Broek'southward earlier idea, introduces concept of atomic number to fix inadequacies of Mendeleev's periodic table, which had been based on atomic weight.[98]

- 1913

- Frederick Soddy proposes the concept of isotopes, that elements with the same chemic properties may have differing atomic weights.[99]

- 1913

- J. J. Thomson expanding on the piece of work of Wien, shows that charged subatomic particles can be separated by their mass-to-charge ratio, a technique known equally mass spectrometry.[100]

- 1916

- Gilbert N. Lewis publishes "The Atom and the Molecule", the foundation of valence bail theory.[101]

- 1921

- Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach establish concept of breakthrough mechanical spin in subatomic particles.[102]

- 1923

- Gilbert N. Lewis and Merle Randall publish Thermodynamics and the Free Energy of Chemical Substances, start modern treatise on chemic thermodynamics.[103]

- 1923

- Gilbert North. Lewis develops the electron pair theory of acid/base reactions.[101]

- 1924

- Louis de Broglie introduces the wave-model of atomic construction, based on the ideas of wave–particle duality.[104]

- 1925

- Wolfgang Pauli develops the exclusion principle, which states that no two electrons around a single nucleus may have the same quantum state, as described by 4 breakthrough numbers.[105]

The Schrödinger equation

- 1926

- Erwin Schrödinger proposes the Schrödinger equation, which provides a mathematical basis for the moving ridge model of atomic construction.[106]

- 1927

- Werner Heisenberg develops the dubiousness principle which, among other things, explains the mechanics of electron motion around the nucleus.[107]

- 1927

- Fritz London and Walter Heitler apply quantum mechanics to explicate covalent bonding in the hydrogen molecule,[108] which marked the birth of quantum chemistry.[109]

- 1929

- Linus Pauling publishes Pauling's rules, which are fundamental principles for the use of X-ray crystallography to deduce molecular construction.[110]

- 1931

- Erich Hückel proposes Hückel's rule, which explains when a planar band molecule will accept aromatic backdrop.[111]

- 1931

- Harold Urey discovers deuterium by fractionally distilling liquid hydrogen.[112]

Model of ii common forms of nylon

- 1932

- James Chadwick discovers the neutron.[113]

- 1932–1934

- Linus Pauling and Robert Mulliken quantify electronegativity, devising the scales that now comport their names.[114]

- 1935

- Wallace Carothers leads a team of chemists at DuPont who invent nylon, one of the near commercially successful synthetic polymers in history.[115]

- 1937

- Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè perform the beginning confirmed synthesis of technetium-97, the first artificially produced element, filling a gap in the periodic table. Though disputed, the element may have been synthesized as early as 1925 by Walter Noddack and others.[116]

- 1937

- Eugene Houdry develops a method of industrial scale catalytic dandy of petroleum, leading to the development of the first modern oil refinery.[117]

- 1937

- Pyotr Kapitsa, John Allen and Don Misener produce supercooled helium-four, the first zippo-viscosity superfluid, a substance that displays quantum mechanical properties on a macroscopic scale.[118]

- 1938

- Otto Hahn discovers the procedure of nuclear fission in uranium and thorium.[119]

- 1939

- Linus Pauling publishes The Nature of the Chemical Bond, a compilation of a decades worth of work on chemical bonding. It is one of the most important modern chemical texts. It explains hybridization theory, covalent bonding and ionic bonding as explained through electronegativity, and resonance as a means to explain, among other things, the structure of benzene.[110]

- 1940

- Edwin McMillan and Philip H. Abelson identify neptunium, the lightest and first synthesized transuranium element, found in the products of uranium fission. McMillan would found a lab at Berkeley that would be involved in the discovery of many new elements and isotopes.[120]

- 1941

- Glenn T. Seaborg takes over McMillan's work creating new diminutive nuclei. Pioneers method of neutron capture and subsequently through other nuclear reactions. Would become the primary or co-discoverer of nine new chemical elements, and dozens of new isotopes of existing elements.[120]

- 1945

- Jacob A. Marinsky, Lawrence E. Glendenin, and Charles D. Coryell perform the first confirmed synthesis of Promethium, filling in the terminal "gap" in the periodic tabular array.[121]

- 1945–1946

- Felix Bloch and Edward Mills Purcell develop the process of nuclear magnetic resonance, an analytical technique important in elucidating structures of molecules, especially in organic chemistry.[122]

- 1951

- Linus Pauling uses X-ray crystallography to deduce the secondary construction of proteins.[110]

- 1952

- Alan Walsh pioneers the field of diminutive absorption spectroscopy, an of import quantitative spectroscopy method that allows one to measure specific concentrations of a cloth in a mixture.[123]

- 1952

- Robert Burns Woodward, Geoffrey Wilkinson, and Ernst Otto Fischer discover the construction of ferrocene, one of the founding discoveries of the field of organometallic chemical science.[124]

- 1953

- James D. Watson and Francis Crick propose the structure of Deoxyribonucleic acid, opening the door to the field of molecular biology.[125]

- 1957

- Jens Skou discovers Na⁺/Grand⁺-ATPase, the commencement ion-transporting enzyme.[126]

- 1958

- Max Perutz and John Kendrew utilize X-ray crystallography to elucidate a protein structure, specifically sperm whale myoglobin.[127]

- 1962

- Neil Bartlett synthesizes xenon hexafluoroplatinate, showing for the first time that the noble gases tin can form chemic compounds.[128]

- 1962

- George Olah observes carbocations via superacid reactions.[129]

- 1964

- Richard R. Ernst performs experiments that volition pb to the development of the technique of Fourier transform NMR. This would greatly increase the sensitivity of the technique, and open the door for magnetic resonance imaging or MRI.[130]

- 1965

- Robert Burns Woodward and Roald Hoffmann propose the Woodward–Hoffmann rules, which use the symmetry of molecular orbitals to explicate the stereochemistry of chemical reactions.[124]

- 1966

- Hitoshi Nozaki and Ryōji Noyori discovered the get-go instance of asymmetric catalysis (hydrogenation) using a structurally well-defined chiral transition metallic complex.[131] [132]

- 1970

- John Pople develops the Gaussian program greatly easing computational chemistry calculations.[133]

- 1971

- Yves Chauvin offered an explanation of the reaction mechanism of olefin metathesis reactions.[134]

- 1975

- Karl Barry Sharpless and group discover a stereoselective oxidation reactions including Sharpless epoxidation,[135] [136] Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation,[137] [138] [139] and Sharpless oxyamination.[140] [141] [142]

Buckminsterfullerene, C60

- 1985

- Harold Kroto, Robert Scroll and Richard Smalley discover fullerenes, a form of large carbon molecules superficially resembling the geodesic dome designed by builder R. Buckminster Fuller.[143]

- 1991

- Sumio Iijima uses electron microscopy to observe a type of cylindrical fullerene known as a carbon nanotube, though earlier work had been washed in the field as early on equally 1951. This material is an important component in the field of nanotechnology.[144]

- 1994

- Starting time full synthesis of Taxol by Robert A. Holton and his group.[145] [146] [147]

- 1995

- Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman produce the first Bose–Einstein condensate, a substance that displays breakthrough mechanical properties on the macroscopic calibration.[148]

21st century [edit]

| | This section is empty. You tin can help by adding to it. (December 2021) |

See also [edit]

- History of chemistry

- Nobel Prize in chemical science

- List of Nobel laureates in Chemistry

- Timeline of chemical elements discoveries

References [edit]

- ^ "Chemical science – The Central Scientific discipline". The Chemical science Hall of Fame. York University. Retrieved 2006-09-12 .

- ^ Kingsley, Grand. Scarlett and Richard Parry, "Empedocles", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition), Edward North. Zalta (ed.).

- ^ Berryman, Sylvia (2004-08-fourteen). "Leucippus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Enquiry Lab, CSLI, Stanford University. Retrieved 2007-03-eleven .

- ^ Berryman, Sylvia (2004-08-15). "Democritus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Inquiry Lab, CSLI, Stanford University. Retrieved 2007-03-11 .

- ^ Hillar, Marian (2004). "The Problem of the Soul in Aristotle'due south De anima". NASA WMAP. Archived from the original on 2006-09-09. Retrieved 2006-08-x .

- ^ "HISTORY/CHRONOLOGY OF THE ELEMENTS". Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ Sedley, David (2004-08-04). "Lucretius". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, CSLI, Stanford University. Retrieved 2007-03-11 .

- ^ a b Strathern, Paul (2000). Mendeleyev'due south Dream – The Quest for the Elements. Berkley Books. ISBN978-0-425-18467-vii.

- ^ Kraus, Paul 1942-1943. Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans 50'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. Ii. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale, vol. II, p. 1, note 1; Weisser, Ursula 1980. Das Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 199. On the dating and historical background of the Sirr al-khalīqa, come across Kraus 1942−1943, vol. II, pp. 270–303; Weisser 1980, pp. 39–72. On the further history of this theory up to the eighteenth century, encounter Norris, John 2006. "The Mineral Exhalation Theory of Metallogenesis in Pre-Modern Mineral Science" in: Ambix, 53, pp. 43–65.

- ^ Weisser 1980, p. 46.

- ^ Isaac Newton. "Keynes MS. 28". The Chymistry of Isaac Newton. Ed. William R. Newman. June 2010.

- ^ Stapleton, Henry E. and Azo, R. F. and Hidayat Husain, Chiliad. 1927. "Chemical science in Republic of iraq and Persia in the 10th Century A.D" in: Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol. VIII, no. vi, pp. 317-418, pp. 338–340; Kraus, Paul 1942-1943. Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans 50'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale, vol. II, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Multhauf, Robert P. (1966). The Origins of Chemical science. London: Oldbourne. pp. 141-142.

- ^ Multhauf 1966, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Marmura, Michael Eastward. (1965). "An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines. Conceptions of Nature and Methods Used for Its Study by the Ikhwan Al-Safa'an, Al-Biruni, and Ibn Sina past Seyyed Hossein Nasr". Speculum. 40 (iv): 744–746. doi:10.2307/2851429. JSTOR 2851429.

- ^ Robert Briffault (1938). The Making of Humanity, p. 196-197.

- ^ Multhauf 1966, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Cosmic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Visitor.

- ^ Holmyard, Eric John (1957). Alchemy. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-486-26298-7. pp. 51–52.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). Nature'due south Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press. pp. 43, 513, 529. ISBN978-0-nineteen-850341-5.

- ^ Davidson, Michael Westward. (2003-08-01). "Molecular Expressions: Science, Eyes and Yous — Timeline — Albertus Magnus". National Loftier Magnetic Field Laboratory at The Florida State University. The Florida State Academy. Retrieved 2009-11-28 .

- ^ Vladimir Karpenko, John A. Norris(2001), Vitriol in the history of Chemistry, Charles Academy

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, Eastward. F. (2003). "Roger Salary". MacTutor. School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ Newman, William R. 1985. "New Lite on the Identity of Geber" in: Sudhoffs Archiv, 69(1), pp. 76-xc; Newman, William R. 2001. "Experimental Corpuscular Theory in Aristotelian Alchemy: From Geber to Sennert" in: Christoph Lüthy (ed.). Late Medieval and Early on Mod Corpuscular Matter Theories. Leiden: Brill, 2001, pp. 291-329; Newman, William R. 2006. Atoms and Alchemy: Chymistry and the Experimental Origins of the Scientific Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Ross, Hugh Munro (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Printing. p. 520.

- ^ "From liquid to vapor and back: origins". Special Collections Department. University of Delaware Library. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ Asarnow, Herman (2005-08-08). "Sir Francis Bacon: Empiricism". An Image-Oriented Introduction to Backgrounds for English Renaissance Literature. University of Portland. Archived from the original on 2007-02-01. Retrieved 2007-02-22 .

- ^ "Sedziwój, Michal". infopoland: Poland on the Web. Academy at Buffalo. Archived from the original on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2007-02-22 .

- ^ Crosland, Thou.P. (1959). "The employ of diagrams as chemical 'equations' in the lectures of William Cullen and Joseph Black". Annals of Scientific discipline. 15 (2): 75–90. doi:x.1080/00033795900200088.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Johann Baptista van Helmont". History of Gas Chemistry. Heart for Microscale Gas Chemistry, Creighton University. 2005-09-25. Retrieved 2007-02-23 .

- ^ a b "Robert Boyle". Chemical Achievers: The Man Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ Georg Brandt first showed cobalt to be a new metal in: Thousand. Brandt (1735) "Dissertatio de semimetallis" (Dissertation on semi-metals), Acta Literaria et Scientiarum Sveciae (Journal of Swedish literature and sciences), vol. four, pages one–10.

Run across also: (1) G. Brandt (1746) "Rön och anmärkningar angäende en synnerlig färg — cobolt" (Observations and remarks concerning an boggling pigment — cobalt), Kongliga Svenska vetenskapsakademiens handlingar (Transactions of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science), vol.vii, pages 119–130; (2) G. Brandt (1748) "Cobalti nova species examinata et descripta" (Cobalt, a new element examined and described), Acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum Upsaliensis (Journal of the Royal Scientific Social club of Uppsala), 1st series, vol. three, pages 33–41; (3) James Fifty. Marshall and Virginia R. Marshall (Spring 2003) "Rediscovery of the Elements: Riddarhyttan, Sweden," Archived 2010-07-03 at the Wayback Machine The Hexagon (official periodical of the Blastoff Chi Sigma fraternity of chemists), vol. 94, no. 1, pages 3–8. - ^ Wang, Shijie (2006). "Cobalt—Its recovery, recycling, and application". Periodical of the Minerals, Metals and Materials Society. 58 (10): 47–50. Bibcode:2006JOM....58j..47W. doi:ten.1007/s11837-006-0201-y.

- ^ Cooper, Alan (1999). "Joseph Black". History of Glasgow University Chemistry Department. University of Glasgow Section of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 2006-04-x. Retrieved 2006-02-23 .

- ^ Seyferth, Dietmar (2001). "Cadet's Fuming Arsenical Liquid and the Cacodyl Compounds of Bunsen". Organometallics. 20 (8): 1488–1498. doi:ten.1021/om0101947.

- ^ Partington, J.R. (1989). A Short History of Chemistry . Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN978-0-486-65977-0.

- ^ Cavendish, Henry (1766). "Three Papers Containing Experiments on Factitious Air, by the Hon. Henry Cavendish". Philosophical Transactions. The University Press. 56: 141–184. Bibcode:1766RSPT...56..141C. doi:ten.1098/rstl.1766.0019 . Retrieved half-dozen November 2007.

- ^ "Joseph Priestley". Chemic Achievers: The Human being Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "Carl Wilhelm Scheele". History of Gas Chemistry. Center for Microscale Gas Chemistry, Creighton University. 2005-09-xi. Retrieved 2007-02-23 .

- ^ "Lavoisier, Antoine." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 24 July 2007 <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9369846>.

- ^ a b c Weisstein, Eric Due west. (1996). "Lavoisier, Antoine (1743–1794)". Eric Weisstein's World of Scientific Biography. Wolfram Research Products. Retrieved 2007-02-23 .

- ^ "Jacques Alexandre César Charles". Centennial of Flying. U.S. Centennial of Flight Committee. 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2007-02-23 .

- ^ Burns, Ralph A. (1999). Fundamentals of Chemistry . Prentice Hall. p. 32. ISBN978-0-02-317351-half-dozen.

- ^ "Proust, Joseph Louis (1754–1826)". 100 Distinguished Chemists. European Association for Chemic and Molecular Science. 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2007-02-23 .

- ^ "Inventor Alessandro Volta Biography". The Smashing Idea Finder. The Great Idea Finder. 2005. Retrieved 2007-02-23 .

- ^ a b "John Dalton". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "The Human Face of Chemic Sciences". Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "December vi Births". Today in Science History. Today in Science History. 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ "Jöns Jakob Berzelius". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemic Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "Michael Faraday". Famous Physicists and Astronomers . Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ a b c "Justus von Liebig and Friedrich Wöhler". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "William Prout". Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ "Hess, Germain Henri". Archived from the original on 2007-02-09. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ "Kolbe, Adolph Wilhelm Hermann". 100 Distinguished European Chemists. European Association for Chemical and Molecular Sciences. 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-x-11. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. (1996). "Kelvin, Lord William Thomson (1824–1907)". Eric Weisstein's World of Scientific Biography. Wolfram Research Products. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ "History of Chirality". Stheno Corporation. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-03-07. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ "Lambert-Beer Police force". Sigrist-Photometer AG. 2007-03-07. Retrieved 2007-03-12 .

- ^ "Benjamin Silliman, Jr. (1816–1885)". Movie History. Picture History LLC. 2003. Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ "William Henry Perkin". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ a b "Archibald Scott Couper and August Kekulé von Stradonitz". Chemical Achievers: The Man Face of Chemic Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E.F. (2002). "Gustav Robert Kirchhoff". MacTutor. School of Mathematics and Statistics Academy of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ Eric R. Scerri, The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance, Oxford Academy Press, 2006.

- ^ "Alexander Parkes (1813–1890)". People & Polymers. Plastics Historical Lodge. Archived from the original on 2007-03-15. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ a b c "The Periodic Table". The Third Millennium Online. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ a b "Julius Lothar Meyer and Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev". Chemical Achievers: The Human being Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemic Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ C.M. Guldberg and P. Waage,"Studies Concerning Affinity" C. K. Forhandlinger: Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiana (1864), 35

- ^ P. Waage, "Experiments for Determining the Analogousness Police force" ,Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania, (1864) 92.

- ^ C.M. Guldberg, "Concerning the Laws of Chemical Affinity", C. M. Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania (1864) 111

- ^ "No. 1858: Johann Josef Loschmidt". world wide web.uh.edu . Retrieved 2016-x-09 .

- ^ "Adolf von Baeyer: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1905". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1901–1921. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1966. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Jacobus Henricus van't Hoff". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face up of Chemic Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E.F. (1997). "Josiah Willard Gibbs". MacTutor. School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ Weisstein, Eric Due west. (1996). "Boltzmann, Ludwig (1844–1906)". Eric Weisstein'due south World of Scientific Biography. Wolfram Research Products. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ "Svante August Arrhenius". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "Jacobus H. van 't Hoff: The Nobel Prize in Chemical science 1901". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1901–1921. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1966. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Emil Fischer: The Nobel Prize in Chemical science 1902". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1901–1921. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1966. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Henry Louis Le Châtelier". World of Scientific Discovery. Thomson Gale. 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ "History of Chemistry". Intensive General Chemistry. Columbia University Department of Chemical science Undergraduate Programme. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ "Alfred Werner: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1913". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1901–1921. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1966. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ "William Ramsay: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1904". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1901–1921. Elsevier Publishing Visitor. 1966. Retrieved 2007-03-xx .

- ^ "Joseph John Thomson". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "Alfred Werner: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1911". Nobel Lectures, Physics 1901–1921. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1967. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ "Marie Sklodowska Curie". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ a b "Ernest Rutherford: The Nobel Prize in Chemical science 1908". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1901–1921. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1966. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Tsvet, Mikhail (Semyonovich)". Compton's Desk-bound Reference. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Archived from the original on 2012-06-30. Retrieved 2007-03-24 .

- ^ "Physics Time-Line 1900 to 1949". Weburbia.com. Archived from the original on 2007-04-30. Retrieved 2007-03-25 .

- ^ "Fritz Haber". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ Cassidy, David (1996). "Einstein on Brownian Motility". The Eye for History of Physics. Retrieved 2007-03-25 .

- ^ "Leo Hendrik Baekeland". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "Robert A. Millikan: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1923". Nobel Lectures, Physics 1922–1941. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1965. Retrieved 2007-07-17 .

- ^ "Søren Sørensen". Chemical Achievers: The Man Confront of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ Parker, David. "Nuclear Twins: The Discovery of the Proton and Neutron". Electron Centennial Folio . Retrieved 2007-03-25 .

- ^ "Solvay Conference". Einstein Symposium. 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-28 .

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1915". Nobelprize.org. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Peter Debye: The Nobel Prize in Chemical science 1936". Nobel Lectures, Chemical science 1922–1941. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1966. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Niels Bohr: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1922". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1922–1941. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1966. Retrieved 2007-03-25 .

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. (1996). "Moseley, Henry (1887–1915)". Eric Weisstein'southward World of Scientific Biography. Wolfram Inquiry Products. Retrieved 2007-03-25 .

- ^ "Frederick Soddy The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1921". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1901–1921. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1966. Retrieved 2007-03-25 .

- ^ "Early Mass Spectrometry". A History of Mass Spectrometry. Scripps Center for Mass Spectrometry. 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-03-03. Retrieved 2007-03-26 .

- ^ a b "Gilbert Newton Lewis and Irving Langmuir". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "Electron Spin". Retrieved 2007-03-26 .

- ^ LeMaster, Nancy; McGann, Diane (1992). "GILBERT NEWTON LEWIS: AMERICAN CHEMIST (1875–1946)". Woodrow Wilson Leadership Program in Chemistry. The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-04-01. Retrieved 2007-03-25 .

- ^ "Louis de Broglie: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1929". Nobel Lectures, Physics 1922–1941. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1965. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Wolfgang Pauli: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1945". Nobel Lectures, Physics 1942–1962. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1964. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Erwin Schrödinger: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1933". Nobel Lectures, Physics 1922–1941. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1965. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Werner Heisenberg: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1932". Nobel Lectures, Physics 1922–1941. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1965. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ Heitler, Walter; London, Fritz (1927). "Wechselwirkung neutraler Atome und homöopolare Bindung nach der Quantenmechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik. 44 (six–7): 455–472. Bibcode:1927ZPhy...44..455H. doi:10.1007/BF01397394.

- ^ Ivor Grattan-Guinness. Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, p. 1266.; Jagdish Mehra, Helmut Rechenberg. The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. Springer, 2001, p. 540.

- ^ a b c "Linus Pauling: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1954". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1942–1962. Elsevier. 1964. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ Rzepa, Henry S. "The aromaticity of Pericyclic reaction transition states". Department of Chemical science, Royal Higher London. Retrieved 2007-03-26 .

- ^ "Harold C. Urey: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1934". Nobel Lectures, Chemical science 1922–1941. Elsevier Publishing Visitor. 1965. Retrieved 2007-03-26 .

- ^ "James Chadwick: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1935". Nobel Lectures, Physics 1922–1941. Elsevier Publishing Company. 1965. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ Jensen, William B. (2003). "Electronegativity from Avogadro to Pauling: II. Late Nineteenth- and Early on Twentieth-Century Developments". Journal of Chemic Didactics. fourscore (iii): 279. Bibcode:2003JChEd..80..279J. doi:ten.1021/ed080p279.

- ^ "Wallace Hume Carothers". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemical Sciences. Chemic Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "Emilio Segrè: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1959". Nobel Lectures, Physics 1942–1962. Elsevier Publishing Visitor. 1965. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Eugene Houdry". Chemic Achievers: The Human Confront of Chemical Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "Pyotr Kapitsa: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1978". Les Prix Nobel, The Nobel Prizes 1991. Nobel Foundation. 1979. Retrieved 2007-03-26 .

- ^ "Otto Hahn: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1944". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1942–1962. Elsevier Publishing Visitor. 1964. Retrieved 2007-04-07 .

- ^ a b "Glenn Theodore Seaborg". Chemical Achievers: The Human Face of Chemic Sciences. Chemical Heritage Foundation. 2005.

- ^ "History of the Elements of the Periodic Table". AUS-e-TUTE. Retrieved 2007-03-26 .

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1952". Nobelprize.org. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ Hannaford, Peter. "Alan Walsh 1916–1998". AAS Biographical Memoirs. Australian Academy of Science. Archived from the original on 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2007-03-26 .

- ^ a b Cornforth, Lord Todd, John; Cornforth, J.; T., A. R.; C., J. W. (November 1981). "Robert Burns Woodward. x April 1917-8 July 1979". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Lodge. 27 (half-dozen): 628–695. doi:ten.1098/rsbm.1981.0025. JSTOR 198111. annotation: potency required for web access.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Medicine 1962". Nobelprize.org. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ Skou, Jens (1957). "The influence of some cations on an adenosine triphosphatase from peripheral fretfulness". Biochim Biophys Acta. 23 (2): 394–401. doi:ten.1016/0006-3002(57)90343-8. PMID 13412736.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1962". Nobelprize.org. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Neil Bartlett and the Reactive Noble Gases". American Chemical Lodge. Archived from the original on Jan 12, 2013. Retrieved June five, 2012.

- ^ Grand. A. Olah, S. J. Kuhn, W. S. Tolgyesi, E. B. Baker, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 2733; G. A. Olah, lieu. Chim. (Bucharest), 1962, 7, 1139 (Nenitzescu outcome); Grand. A. Olah, W. South. Tolgyesi, Due south. J. Kuhn, M. Due east. Moffatt, I. J. Bastien, East. B. Bakery, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 1328.

- ^ "Richard R. Ernst The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1991". Les Prix Nobel, The Nobel Prizes 1991. Nobel Foundation. 1992. Retrieved 2007-03-27 .

- ^ H. Nozaki, S. Moriuti, H. Takaya, R. Noyori, Tetrahedron Lett. 1966, 5239;

- ^ H. Nozaki, H. Takaya, S. Moriuti, R. Noyori, Tetrahedron 1968, 24, 3655.

- ^ W. J. Hehre, West. A. Lathan, R. Ditchfield, Thou. D. Newton, and J. A. Pople, Gaussian lxx (Quantum Chemistry Program Commutation, Program No. 237, 1970).

- ^ Catalyse de transformation des oléfines par les complexes du tungstène. 2. Télomérisation des oléfines cycliques en présence d'oléfines acycliques Die Makromolekulare Chemie Volume 141, Consequence 1, Date: 9 February 1971, Pages: 161–176 Par Jean-Louis Hérisson, Yves Chauvin doi:10.1002/macp.1971.021410112

- ^ Katsuki, Tsutomu (1980). "The first practical method for asymmetric epoxidation". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 102 (xviii): 5974–5976. doi:10.1021/ja00538a077.

- ^ Hill, J. G.; Sharpless, K. B.; Exon, C. M.; Regenye, R. Org. Synth., Coll. Vol. 7, p.461 (1990); Vol. 63, p.66 (1985). (Article)

- ^ Jacobsen, Eric N. (1988). "Disproportionate dihydroxylation via ligand-accelerated catalysis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 110 (half dozen): 1968–1970. doi:x.1021/ja00214a053.

- ^ Kolb, Hartmuth C. (1994). "Catalytic Asymmetric Dihydroxylation". Chemic Reviews. 94 (8): 2483–2547. doi:10.1021/cr00032a009.

- ^ Gonzalez, J.; Aurigemma, C.; Truesdale, L. Org. Synth., Coll. Vol. 10, p.603 (2004); Vol. 79, p.93 (2002). (Article)

- ^ Sharpless, K. Barry (1975). "New reaction. Stereospecific vicinal oxyamination of olefins by alkyl imido osmium compounds". Periodical of the American Chemic Society. 97 (8): 2305–2307. doi:10.1021/ja00841a071.

- ^ Herranz, Eugenio (1978). "Osmium-catalyzed vicinal oxyamination of olefins by N-chloro-N-argentocarbamates". Journal of the American Chemical Gild. 100 (11): 3596–3598. doi:x.1021/ja00479a051.

- ^ Herranz, E.; Sharpless, K. B. Org. Synth., Coll. Vol. seven, p.375 (1990); Vol. 61, p.85 (1983). (Commodity)

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1996". Nobelprize.org. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-02-28 .

- ^ "Benjamin Franklin Medal awarded to Dr. Sumio Iijima, Director of the Inquiry Center for Advanced Carbon Materials, AIST". National Establish of Advanced Industrial Scientific discipline and Engineering science. 2002. Archived from the original on 2007-04-04. Retrieved 2007-03-27 .

- ^ Commencement full synthesis of taxol ane. Functionalization of the B band Robert A. Holton, Carmen Somoza, Hyeong Baik Kim, Feng Liang, Ronald J. Biediger, P. Douglas Boatman, Mitsuru Shindo, Chase C. Smith, Soekchan Kim, et al.; J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1994; 116(4); 1597–1598. DOI Abstruse

- ^ Holton, Robert A. (1994). "First total synthesis of taxol. 2. Completion of the C and D rings". Journal of the American Chemic Guild. 116 (iv): 1599–1600. doi:10.1021/ja00083a067.

- ^ Holton, Robert A. (1988). "A synthesis of taxusin". Periodical of the American Chemical Order. 110 (19): 6558–6560. doi:10.1021/ja00227a043.

- ^ "Cornell and Wieman Share 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics". NIST News Release. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-03-27 .

Further reading [edit]

- Servos, John W., Physical chemistry from Ostwald to Pauling : the making of a scientific discipline in America, Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-691-08566-viii

External links [edit]

- Eric Weisstein's Earth of Scientific Biography

- History of Gas Chemical science

- list of all Nobel Prize laureates

- History of Elements of the Periodic Table

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_chemistry

0 Response to "what advances were made in the field of medicinal chemistry during the period from 1700 to 1900?"

Post a Comment